Science background gives teachers more in-depth information on the phenomena students explore in this unit. Below is an excerpt from the science background on glacier motion.

Types of Glaciers

There are two types of glaciers: continental glaciers and alpine glaciers. Continental glaciers, also known as ice sheets, are masses of ice and snow that permanently cover an extensive area of land in Earth’s polar regions. For example, the Antarctica ice sheet has existed for at least 40 million years, and it is 4.8 kilometers (3 miles) thick in places. Scientists estimate that if it were to entirely melt, it would cause sea levels around the world to rise 60 meters (200 feet).

In addition to continental glaciers, there are also alpine glaciers, which form on mountains and flow down valleys. They form at high altitudes where the air is thin and temperatures are low. The ice moves downward by riding over a layer of meltwater at the glacier’s base.

At the top of the mountain, alpine glaciers have a kind of potential energy called gravitational energy, which is the energy stored in an object as a result of its vertical position or height. The taller the mountain, the more gravitational potential energy the glacier has. This is a cause-and-effect relationship. The height of the mountain causes the amount of energy stored in the glacier to change. Once the glacier starts moving, that gravitational potential energy transforms into kinetic energy. As the glacier moves down the mountain, gravitational potential energy is constantly transforming into kinetic energy.

Even though they are made of solid ice, glaciers flow like powerful rivers, pulled downward by their own weight. Weight is the gravitational force exerted on an object by a planet or moon. Gravity is the attractive force between all matter. Gravity is what keeps you on Earth and pulls all objects back toward Earth’s surface.

A Changing Landscape

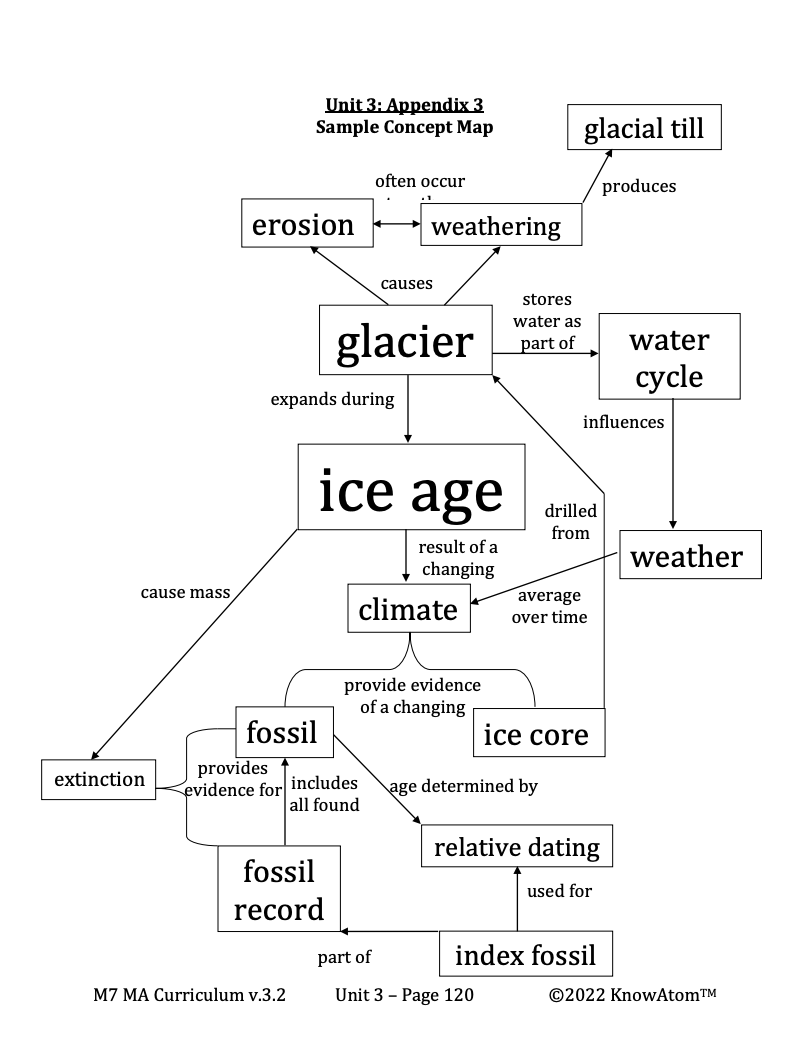

Weathered Earth materials become frozen to the bottom of the glacier and get carried along with it. Those pieces of sediment get dragged over the land, weathering the land in the same way that sandpaper wears down and smoothes objects. They can also be deposited far away from their original location. The eroded sediment that is deposited as glaciers retreat and expand is called glacial till. Moraines are narrow ridges that are left behind from glacial till gathered on a glacier’s surface or sides.

As glaciers erode Earth materials, they carve out the land beneath them. A result of this is that the movement of a glacier can significantly change the landscape. For example, the movement of glaciers can create glaciated valleys. These valleys are usually very deep with vertical walls. As glaciers recede, they can also create fjords, which are long and narrow valleys. They are often U-shaped, with steep sides and a rounded bottom.

When seawater fills the land, it creates fjords. Lakes can also form when pieces of glacial ice break off and melt. These lakes are usually shallow and filled with sediment from the glacial ice.

Part of the Global Water Cycle

One reason that scientists study the Antarctic glaciers is that the glaciers are an important part of the global water cycle. The water cycle is the circulation of water through the hydrosphere from Earth’s surface to the atmosphere and back. Water is continually changing from a solid to a liquid or gas and back to a solid depending on the amount of thermal energy (heat) present from the sun.

Glaciers currently cover 10 percent of the planet and hold almost 70 percent of the world’s fresh water. The water held in glaciers is in “storage.” Some of the water in Antarctica has been there for thousands of years. Because of this, glaciers are considered reservoirs. Reservoirs are places where water is stored for a period of time, including glaciers, oceans, and the atmosphere.

Water in glaciers is solid ice. Remember that solids have the least amount of thermal energy of all of the states of matter. Water molecules in solid ice are closely packed together and vibrate in place.

Water in the atmosphere is called water vapor, which is water’s gas state. Much of the water in the atmosphere cycles between liquid water and water vapor through two processes: precipitation and evaporation. Evaporation is the process of liquid water changing into water vapor. Water evaporates when enough thermal energy is present. Like all liquids, the atoms and molecules that make up liquid water are less tightly packed than they are in a solid. They are in constant contact with one another, but they have enough energy to slide past one another.

When thermal energy is added to liquid water, the atoms and molecules begin to speed up. When enough thermal energy is added, the atoms or molecules will move so quickly that the water expands, becoming water vapor.