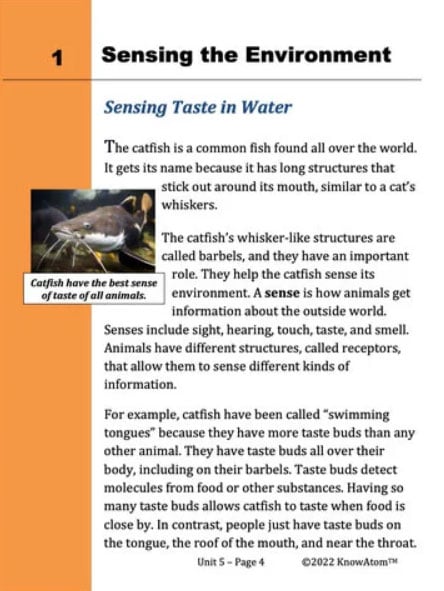

Science background provides teachers with more in-depth information on the phenomena students explore in this unit about organisms and their environment. Below is an excerpt of this section from the lesson on selecting traits phenomena.

Heredity explains why baby catfish have barbels, baby hummingbirds have long, thin beaks, and baby giraffes have long necks, just like their parents. All of these are inherited traits.

The long, thin beaks of a hummingbird and the long neck of a giraffe are both examples of adaptations because they are traits that help an organism survive in its environment. An adaptation can take many generations to spread through a population. Over time, animal and plant populations can slowly adjust their diets, physical forms, and behaviors.

Minor changes to an organism’s environment can influence its ability to pass on its traits. Increased precipitation, competition for food, or invading species create situations in which only the “strongest” plants and animals survive. An organism that overcomes these minor challenges passes on its genes to the next generation. Sometimes these stresses lead to the creation of new species. New species appear when there are environmental stresses over a long period of time.

For example, there was a time, millions of years ago, when there were no giraffes. Instead, horse-like creatures, with checkered spots and short necks, roamed the African grasslands. There wasn’t much food for the short-necked animals to eat. A ground shrub was a rare find. All of the food was high in the trees. Not all of the short-necked creatures could reach the trees. Only those with the longest necks could reach the bottom-most branches. The individuals with the shortest necks had to compete for the little bit of ground food. Some were no longer able to get enough food, and died off. With each generation, necks grew longer and longer until all of the animals could eat from the tallest trees in Africa.

This is called natural selection—the theory that organisms well fitted to their environments will have offspring and pass on useful adaptations. Those organisms that cannot adapt to their environment don’t reproduce and die out over time.

The slow buildup of adaptations that leads to a new species is called evolution, a field of study associated with English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Darwin made the connection after a survey expedition to South America, Australia, and the Galapàgos. He was particularly interested in the similarities and differences between animals in various locations, such as what made a South American mockingbird different from other species of mockingbirds.

Hints of his theory of evolution came from his observation of finches on the Galapàgos. He observed that about a dozen different finch species existed on the island, and each had a beak specific to its diet. It made him wonder how new species arise. The finches, which were confined to the island for many centuries, seemed to have descended from one species “taken and modified for different ends.”

According to evolution, one common ancestor of life on Earth gave rise to the diversity that we see documented in the fossil record and around us today. The theory of evolution suggests that we're all distant cousins: humans and oak trees, hummingbirds and whales.

Further evidence for evolution came from the field of genetics. Evolutionary biologists can identify specific genes and trace how they mutated through several related species. Human ears, for example, can be traced backward on the evolutionary timeline to fish.

A common fuel for evolution is new types of environments. For instance, when the common ancestor of Darwin’s finches traveled to the Galapàgos Islands, the population branched out as certain members became better at finding different food sources. One type of bird was the common ancestor of several new species.