The Next Generation Science Standards are changing what science classrooms around the country should look like.

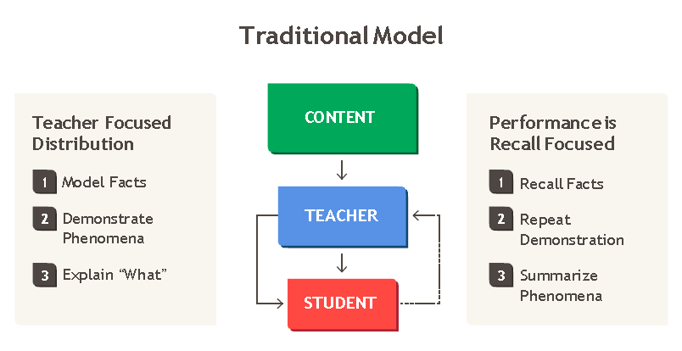

For generations, our classrooms have run on a simple principle: The teacher knows the material, and the students do not. We call this the traditional model. It involves the teacher covering material with the students, who will demonstrate their understanding by essentially mirroring or repeating the teacher’s words or actions to show what they have absorbed.

The traditional model of instruction has the teacher handing content to students in the form of modeling facts, demonstrating phenomenon and explaining “what’s going on.” The students respond and prove their knowledge by recalling those facts, repeating the demonstrations and summarizing the phenomena they see.

This description isn’t intended to be negative; it’s simply a model of education that we believe society is outgrowing. We want to see a shift away from this model of STEM instruction, where content has to flow through a teacher. The idea that the teacher's role is to be the specialist, the sage, is an outdated one.

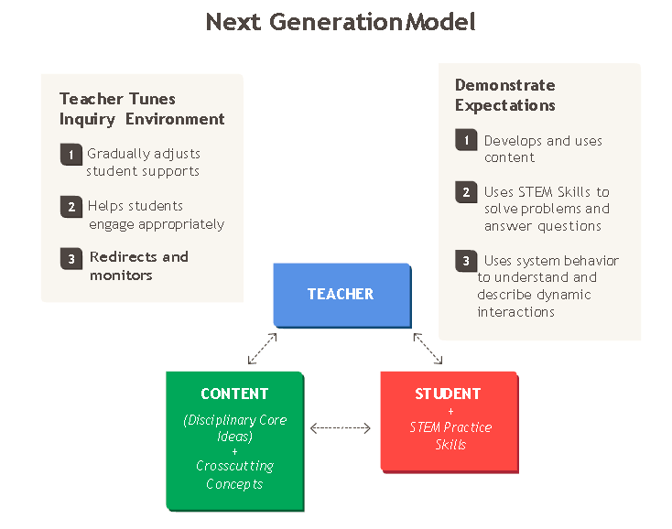

In its place, we advocate a model in which students engage directly with ideas and content, using their higher order thinking skills – creating, evaluating and analyzing – wherever and whenever possible.

The next generation model of science instruction removes the teacher from the role of distributor of knowledge. Instead, the teacher tunes the inquiry environment, adjusting student supports, helping students engage with materials in appropriate ways, and monitoring and redirecting where necessary. Students, for their part, develop and use the content with which they are interacting, hone their STEM skills and explain dynamic interactions through a systems behavior lens.

In the new model of education, which steers clear of this teacher-as-sage archetype, the teacher helps students to understand and develop their roles as scientists or engineers, as well as adjusting the supports around the content.

Our expectations of students are very different in this next generation model as well.

Students will have to develop their science and engineering practice skills in order to interact with the content. The student’s job will be to ask questions and identify problems.

To further student development of these practices, each Next Generation Science Standard has a performance expectation and is broken into disciplinary core ideas (content), crosscutting concepts (big ideas that reach across and connect domains), and practices. That way, the new model of instruction can account for the wide range of student needs and the way students learn: by developing and using content themselves and honing their practice skills, yes, but also by having the teacher there to help them engage appropriately, gradually removing student support and monitoring where necessary.

That’s why these new standards are framed as performance expectations: what students must be able to do, not just know. In the next generation model of instruction, students who actively use their STEM practice skills are able to access content and crosscutting concepts.

In this new student-centered environment, students will also be required to demonstrate the skills they learn to use. Students will still need to understand and remember content, but with the added condition that they must be able to describe it in terms of its dynamic interactions of other pieces of content.

A Foundational Shift

Foundationally, these are the ideas that give rise to STEM, and these are the skills students will need to engage in STEM as a cycle:

- Pose a hypothesis

- Develop an experiment

- Gather data

- Draw conclusions

If you’re beginning to see that these Next Generation Science Standards represent a lot of change, you’re correct. As a leader – whether you're a teacher leader or an administrator leader – you need to understand that there's a lot of foundational shifting necessary to transform America’s science instruction from that of a rote learning model to that of a deeply interactive, critical-thinking environment.

This is not to say that in an inquiry environment we will see absolutely no demonstration or explanation, because that isn’t true. Demonstration of important phenomena will not disappear simply because we switch to this new model. However, the most important thing in an inquiry environment is that students develop specific inquiry skills, which are the science and engineering practices.

As these shifts happen, there will be a lot of change to manage, as well as potential confusion and misaligned expectations on the parts of teachers, administrators, parents, and even students.

If we don’t want these questions to derail even the best of efforts, we will need to synchronize those efforts and place a priority on making this new model of instruction the norm in our classrooms.

We will need to ensure we share similar definitions and values, and that we’re all on the same page regarding what we’re actually trying to accomplish.

This post was updated on 8/21/17.