"We're in a 21st-century innovation economy. Ideas rule the day. We need to really think about our schools in a way that help students just change the world. Actually help them to change the world, not just simply be prepared to live in it." -Scott Morrison

In this transcript from a live interview with KnowAtom CEO Francis Vigeant, Scott Morrison, Director of Curriculum & Instructional Technology in the Marchester-Essex school district in talks about:

- "Building back” all the way from kindergarten to prepare kids for STEM careers

- The difference between knowing and engaging in STEM practices

- Similarities between the order of the process of writing and the order to science ed practices

- Focusing on the “why” of education

- The biggest challenges in making the switch to the Next Generation Science Standards

Francis Vigeant: My name is Francis Vigeant, and I have with me today the Director of Curriculum Instruction for Manchester-Essex Regional School District, Scott Morrison.

Scott Morrison: Hey, Francis.

Francis Vigeant: Hey, Scott. How are you?

Scott Morrison: Good, how are you doing today?

Francis Vigeant: Good. For everyone out there, I'm really happy to have Scott with us today, because Scott is not only a teacher with 22 years of experience, starting in urban education as a math/science teacher, but he's gone on to spend eight years as a principal, and then another eight years as director of curriculum instruction through a variety of different kinds of districts, from urban to suburban.

He is currently wrapping up his PhD in organizational leadership in education from Northeastern University. We could go on and on, but thanks, Scott, for joining us, and I'd like to jump right in here and just let folks know that if you're on the live session, we are going to take question-and-answer for the last 10 to 15 minutes at the end.

If you're from Massachusetts, you probably know Scott, perhaps through the Northeast STEM network, perhaps through a planning team for the Massachusetts State STEM Summit, and as a STEM Advisory Board member. Scott, thanks for joining us.

Scott Morrison: Thank you, Francis. I'm happy to be here and thrilled to be part of this important conversation.

Francis Vigeant: Thanks. You and I collaborated on some slides for today's presentation. The first slide that you sent was, "Here is what we know." When we think about sharing your experience, going from perhaps a traditional model to a next-generation model instruction, your district is seeing evolution over time. Can you share with us what you mean by “what we know” and why this is important?

Scott Morrison: Certainly. I think as an umbrella comment maybe to these four bullet points on this slide, I think as we think about public education, and we think about the way of the world and the direction that we know we need to head in, I think it's not so much what our students know, it's what can they do with what they know.

When you think about that, we're in a 21st-century innovation economy. Ideas rule the day. We need to really think about our schools in a way that, as you can see on the slide, we need to help students just change the world. Actually help them to change the world, not just simply be prepared to live in it. I think, for a long time, I think back to my years as a teacher 20-some odd years ago. I think maybe we were doing a little bit more of that — preparing kids to live in the world.

I think the economy that we're in nowadays, and just the way that the world is operating, we really need to prepare our students to change the world. I think the way that you do that and we'll talk about this. You and I have had these conversations through our STEM Squared experience together. I think the way that we do that is we really need to shift the focus of school from the mere acquisition of knowledge and more towards and understanding of the learning process.

That ties in with that idea of children having knowledge of what they can do with the information that they have, not just having the information. In finding the tools and delivering the professional development to teachers where they can develop the creativity, critical thinking, problem solving, and reasoning skills needed for the 21st- century within our students. I think that sets the stage for a lot of the focus of our conversation today.

Francis Vigeant: You mentioned this 2028. When you think 2028, what's the significance of that?

Scott Morrison: Yes. I know. They have a big red curtain and the big grand opening here of 2028. So 2028, I'm giving a lot of thought to this. I'll be moving into a superintendency in July of next year, and as I was thinking about that position and thinking about that role that I'll be going into, when I begin that role, students in kindergarten next school year, will graduate in 2028.

When I really stopped to think about that — that's an awe-inspiring number, when you think about that. We don't know what the world's going to look like six months from now, 12 months from now, let alone 12 years from now when kindergarten students are graduating from high school and walking off with their diplomas. If we had to think about what type of an educational model that we wanted to design and build, I really think we need to think about it with that number in mind.

I think, unfortunately, the standardized world that we live in, we tend to only think month-to-month in terms of the work that we're doing because of the many mandates we have put upon us in our classrooms and in our schools. I think we need to have the long view on this and think about when students walk off our fields, or walk out of our auditoriums, or off of our stages in 2028, what will the world look like then? What will students need to know and be able to do in order to compete in the workforce at that point?

I think if we stop to have those big conversations — and we're starting to have those conversations where I am now, and I'm looking forward to having those conversations when I transition into a new role as well. I think we need to think about, “How do we build that back?” Whatever that is, how do we build that back in high school, and middle school, and in elementary school all the way down to kindergarten?

What I keep coming back to is this idea of what we talked about on the first slide. Yes, content is important, but I think teaching students how to learn and teaching them how to prepare themselves for understanding the world that they'll be going into, and what are the infrastructure skills that they need in order to learn? I think that's a key part of what we'll talk about today.

Francis Vigeant: I think that's the perfect spot to really begin diving into Next Generation Science Standards and the idea behind Next Generation Science Standards, and one of the key transitions is really this new definition of effective science instruction or we could even say STEM instruction. I'd like to read that and get your thoughts on it, and what that has meant to your community, and what you think that means to the broader community.

Effective STEM instruction capitalizes on students’ early interest and experiences. It identifies and builds on what they know and provides them with experiences to engage them in the practices of science and sustain their interest. That's neither of our definitions, but that's the National Research Council's definition that became infused in this NGSS process. What are your thoughts on that?

Scott Morrison: I think it's spot on. I really do. I think that's exactly the point that I'm trying to make with that idea of 2028. I think engaging students in the practices of the work that they're doing. Particularly, this is a phone call about science and technology engineering, so certainly engaging students in the practices of science, technology, and engineering, and we do have a scientific method and an engineering-design process.

I think if we can develop a way for our students to think in that manner. To think in that sort of process-and-practice manner. A process is just an ordered set of practices. I really think that the more we can focus on that, and I think this is a good slide here that you just put up as well — that's the difference between as it says here, knowledge creation versus information consumption.

That picture on the bottom with the matching gloves and shirts, I think that was probably for some glossy magazine somewhere. That's just information consumption. There's not a lot of knowledge being created there. Kids need to be able to manipulate ideas and thoughts in their mind and figure out how they want to move forward. When I think about a practice, practice connects skill to content. It's the bridge, right? It's the bridge between those two things.

As you have up on the slides there, right there are the engineering practices. Those are the practices that we want our students to engage in in engineering. If you look at those practices, that really carries through many parts of their educational experience. You talked about higher-order thinking. If we can get students to think in this higher-order manner where they're remixing and creating ideas and manipulating those ideas in their head to create new knowledge. That, I think, will have profound effects for the work that we do in education as we move towards the future.

I often make the connection to, and I don't know if we do this enough in education. I think not only do we need to make sure we engage our students in the practices of science, technology, and engineering, but then on a bigger scale, as we think about our teachers and making sure that they have the tools and the instructional practices that they need, we need to allow them to engage in the practices of education also.

Again, if we think of this idea that a practice connects skill to content, I think lawyers and doctors have it right. They call what they do a practice. They have a medical practice or a law practice. They engage in the practices of medicine. They engage in the practices of law. People can do the same thing with our teaching staff. I don't know why it's odd for us to say we're engaging in the practices of education.

As educators, we should be using that language. I think the more that we can do that, I think we have a better chance of moving the needle. When we think about this idea of engaging the practices and really moving the needle forward or ahead in terms of the work that we're doing with our kids.

Francis Vigeant: So we think about that idea: That now, with Next Generation Science Standards, we have really clearly defined practices. You mentioned processes, so these being the practices of science and engineering, and processes being the scientific process or the engineering-design process where these practices come together.

Among your peer group. Among your teachers. Among the different experiences you've had as you've been implementing these practices in the classroom for teaching and learning — what is that transition like? What does it feel like? Is it natural? I feel like one of the challenges even you mentioned for a glossy magazine. When you look at the glossy magazine, this is the picture of science instruction.

Scott Morrison: Right. Exactly.

Francis Vigeant: If it's not this, it's a child with some goggles and an exploding volcano. How do you get beyond that?

Scott Morrison: Yeah. It's a great point that you bring up. I would say I remember a few years ago, I did a Google image search for engineer. Engineering, or engineer, or whatever the case may be. And the first picture that came up was Mickey Mouse on a train with an engineering hat on, like a train conductor/engineer hat on. It's this idea of the imagery around this; oftentimes, I think images can be very powerful, and if that's what science is supposed to look like, and I'm not saying it is, where it's next to the information-consumption box there. That's not what science should necessarily look like, but that's the image that we're surrounding and that's the picture that we're building in people's minds.

That's certainly the wrong image. I think we need to go about changing that. In terms of the real pragmatics we have on the ground, I think really developing an understanding with staff and doing this in a way that you bring people together, and you have these conversations. You ask them about where do they feel they need to grow professionally? I think STEM Squared is a great example of this. STEM Squared is a great example of this, because when we put that program together, we had a lot of people turn out for science-professional development. High-quality, science-professional development.

They were coming on their own time and doing their best to make it work. That, I think, told me that folks really need — especially at the elementary level — really need to develop a stronger understanding of what it's like to teach science, technology, and engineering standards. I think at the heart of this is developing within kids and teachers.

Rick Romelli says this, and I think it's so true: "Meaning-making is the root of perseverance." As students make meaning, they'll continue to persevere with the work that they're doing. I think the same holds true for our teachers as well. "Meaning-making is the root of perseverance." As we deliver the professional development to our teachers and we start to have the conversations about this. We're going to talk about the why a little bit later on in this, but I think focusing on why this is important is something that really helps to move the conversation, and we'll jump on that a little bit more a little bit down the road on this presentation today.

Francis Vigeant: Before we get to the whys, I guess the difference — and I think that that's maybe a point that's worth pointing out here, when you look at these two pictures — really, what's the difference? I know that you're saying knowledge creation versus information consumption, but if you think about it, I think maybe you've provided this slide, and I thought this was really interesting. How knowledge does not equal understanding. What is it that's the difference? Is there something that stands out to you here?

Scott Morrison: Sure. If you can go to that bike slide for a second, I think that might be two ahead. Yeah, that one there. That's a great video. I think it's on YouTube. It's called “The Backwards Bicycle.” As folks get a chance to watch that, I would highly recommend it. I think the implications to education and the work that we do on a daily basis is highly correlated to the gentleman who put this video together.

As you can see in that picture of the bike, there's a gear there. He's an engineer, I think by trade, and he had the folks in his office area, or garage, or wherever he was working out of reverse the handle bars and the tires. So if you're turning the handlebars left, as you can see in that picture, the tire went to the right. This idea of when everyone says, "It's as easy as riding a bike," or, "It's as simple as riding a bike," well, if you think about having the knowledge of riding a bike, well, that doesn't automatically equal understanding, because there's great pictures and video of the gentleman trying to ride this bike, and it took him months to undo in his head the habit that he had developed of how to ride a bike to learn how to actually ride this backwards bicycle.

Then this great video at the end of that YouTube picture or YouTube link where he goes back to ride a regular bike and people are looking at him like, "Why can't this guy ride a bike?" and it's because he had for so long worked on riding a bike this way. He then had his son ride the backwards bike, and his son is able to do it in a much quicker time span. What moves knowledge to understanding is this idea of practice.

The knowledge of how to ride a bike — if you just got on this bike that, doesn't mean you're going to actually understand how to ride it. You actually have to engage in the practices. In Gladwell's quote there, which I think is so fitting, "Practice isn't the thing you do once you're good; it's the thing that makes you good."

If you go back to that previous slide, Francis, I think that will correlate. This thing here — this quote from Valerie Strauser — I read this online, and it just so stuck out to me in terms of, "When kids understand, how their minds sort, store, retrieve, integrate, and relay information. They know how to create knowledge and sometimes even wisdom."

Again, that's that idea of moving beyond just, "Here, remember this; hold onto this information." It's really developing the executive functioning within our kids so they have an ability to figure out how to find that information, how to organize and store that information. How to access that information so that they can start to put it together. That all happens in practice.

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm. When you talk about it, yeah, it makes perfect sense. I guess the question then is, what is the bike that as educators we've all learned to ride versus the next generation bike that we all have to learn to ride and making that shift?

Scott Morrison: Yeah. Well said.

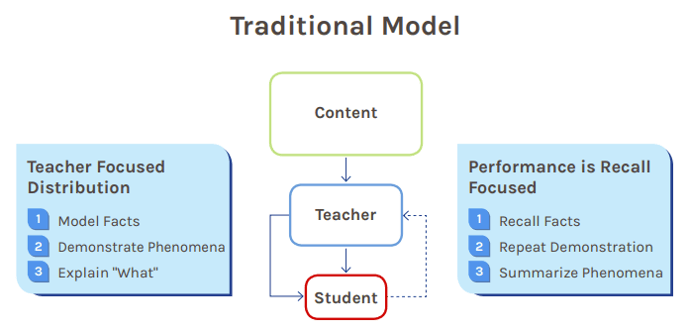

Francis Vigeant: This is a slide that we often use at KnowAtom to talk about the traditional model of science instruction that I think we're all taught as educators traditionally. I think this is changing, so I don't want to paint with too broad of a brush, but the idea that content flows through a teacher whose role it is to be an expert, and that teacher then plays the role of expert by getting on the stage and modeling the facts, explaining why, demonstrating phenomena.

Then the students, being good students, turning around and being able to bring back what they've seen, and do that for recall or repeat. Summarizing the phenomena. And so that's — I think at least at KnowAtom — that's the picture of the bike that we have. What are your thoughts?

Scott Morrison: I think that's a fair assessment. Again, I don't want to paint with a broad brush either, so I'll speak to my experience. When I think about my experience as a fifth grade science teacher, as a 21-year-old fifth grade science teacher when I was hired. Fresh out of college. That was an absolute in my life for a while, because I didn't know any different.

I think it's a model particularly around science, maybe not in every single subject area. I would say particularly at the elementary level, you tend to see this, and it's not the teacher's fault. It is clearly not the fault of a teacher, because that's perhaps the way that they were trained. In my mind, I don't think we've provided the tools and the instructional practices in science — again, particularly at the elementary level — so people can think about how they deliver their information differently.

To me, in this traditional model, we're bypassing the brain of both the teacher and the students. It's just like, "Here's the information; let me transfer my notes into your notebook and we'll call it a day." I think that's just because that's been the model that had been pushed or whatever the case may be, we have not provided the appropriate amount of training, again to our elementary staff — and again, that's just speaking for me and my experiences. I don't know what it's like in the rest of the world. I'd be interested to hear if you we get enough time at the end, I'd like to talk to some folks, but I think that's where it's incumbent upon school leaders to make sure that we are providing the training and development, because it is that important.

I think shame on us and public ed that, again, in my experience, the majority of kids don't get any sort of organized science until sixth grade in a lot of places. This is me now talking to people outside of my district and then having conversations with colleagues from across the state. Science — when I came here to this district, we did an audit. We did a time audit to try to figure out, "Where are we spending our time?" In some cases, science was 2:30 on a Friday, and that's really not science, right? That's just being able to say you did some science.

Again, that's not the teacher's fault. It's the way that things have been set up in the past, and I think we need to make a conscientious effort to go about and changing this because — again, if we go back to this idea of practices and higher-order thinking — science, technology, engineering, math: These are the great subjects for us to do this in.

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm. I was just going to ask about that, because when you think about these next-generation science and engineering practices which are now a part of the Next Generation Science Standards, it's one of the foundations. It's a part of the standards here as of January 26th in Massachusetts — science and engineering practices.

They've been part of your district at least as far as I know we've been there. How do you see these crossing over into other disciplines? Particularly ELA and math, where I think it doesn't surprise me at all that you did a time audit and found science being low man on the totem pole, especially when No Child Left Behind was much more in-focus than it is now, but nonetheless, it created these habits.

The thing is, there is an element of oversight there in the sense that is science and engineering in these practices useful to the other disciplines? Is it a forum for them in some way?

Scott Morrison: I think it certainly is and I think, again, I have found when you talk about pragmatically. When I've done presentations rather around the district here in terms of sharing information about the new science and engineering standards and really trying to help staff make meaning. Right, again if we go back to Romelli’s quote on, "Meaning-making is the root of perseverance," I think one of the things I connected this to is, I would say to the teachers, "Where else do you use practices?"

Folks think on it a minute, and I say writing practices and processes, because we talk about a process just being an ordered set of practices. They said, "Oh, well, we have a writing process." I said, "Exactly. So what's your writing process?" and they say, "Well, you do pre-writing and then you do some drafting and editing," and whatever the order is. That's not on my brain right now, but the whole writing process is a process that folks are familiar with.

So I say to them, "Okay, does the order matter?" "Yup, the order matters. Absolutely it matters." Some kids like to think their final copy is their first draft. The order definitely matters. When we make that connection to the writing process and we say to them, "Right. So the writing process is just an ordered set of practices that students engage in when they're writing," it's no different in science and engineering.

We have a set of practices here that we want our students to engage in, and when I look at these practices — if you just look up those Bloom words, analyzing, planning, developing, constructing, evaluating, communicating. That's all higher order. You go back to Bloom, 1956 — Bloom's taxonomy, his tiered taxonomy of cognitive thinking — and I think when we think about that, I think too often school is focused on more of that rote and I think if we can't... Beautiful. Hey, nicely timed. I think if we can...

Francis Vigeant: I'm telling you.

Scott Morrison: That's good. I think if we can move our students up into that higher-order thinking — creating, evaluating, analyzing, and I love that idea of taking information apart — and exploring the relationships, and critically examining, and making judgments, and using information to create something new: These are life skills, right?

I want my nieces — when they graduate from college and head off to the world — I want them to be able to analyze their first contract and evaluate a home inspection if they're buying a home or whatever the case may be. Those are skills that we certainly need to cultivate, and they're beyond just skills for school. They're life skills in many ways. This is where I see science being just fertile ground for us to really begin to develop this.

Again, I'll go back to my number of 2028. This is exactly what I'm talking about. What will the world look like in 2028? I don't know if the kids are going to have to memorize their 50 states and capitals by 2028. I'm not sure if that will still be in the curriculum, but boy, I bet you they're certainly going to have to know how to evaluate, create, and analyze, and construct and communicate and collaborate and do all those other things so we can build that infrastructure in from K through 12. Boy do we have a good chance of really making some changes here.

Francis Vigeant: Well, I'm glad you brought up higher-order thinking, because this is a slide we often use just to talk about that, and you'll notice that we've reorganized it. Your Bloom's taxonomy is traditionally a six-level: Remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create, right?

Scott Morrison: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Francis Vigeant: What we've done is really thinking about the role of science and engineering through the lens of Next Generation Science Standards, and then I think really true to what the disciplines are that creating, evaluating, and analyzing happen simultaneously. To your point, you don't go to buy a house and say, "Well, okay. We're only going to analyze; we're not going to evaluate." These things happen simultaneously, and I think the creative aspect too oftentimes is in finding a solution because nothing is really perfect.

That could be a house you walk into. We're from New England, so there's an awful lot of older homes here, and nothing's perfect. You have to have creative solutions sometimes. I think about what you were just sharing also, and I think about some of a discussion I had with some of our partners in Israel and in our programs in Iraq, because they said what's really interesting is that these skills — to be able to create, evaluate, and analyze — are social-emotional coping mechanisms, really.

Scott Morrison: That's exactly right.

Francis Vigeant: They said that. I had never really thought of it that way, and I think in your example of buying a house or something like this, it's like, "How often do you have all the resources you'd need for anything in your life?"

You think about sitting down to write an essay, even. It's like you have to brainstorm. You don't even have all the ideas right? It's a creative process. Then there's an evaluative and analytical piece of this too, and norming, and that's ELA.

Anyway, so not to riff too much on this, but I think you bring up a really great point. One of the other slides that you provided, which I'd like to share with folks before we move a little further down the road here in our discussion, is this idea of...

Scott Morrison: I love that idea.

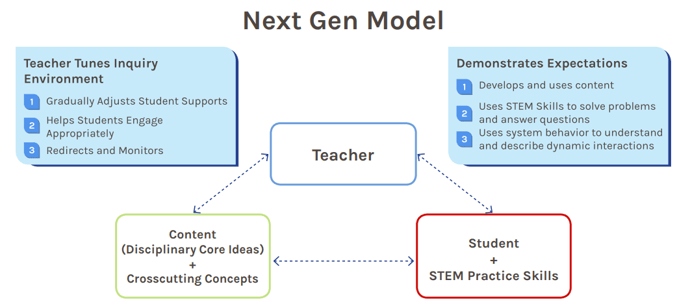

Francis Vigeant: How we create this environment and, as you mentioned, KnowAtom, so that was nice of you. What do you mean with this diagram and how we create a learning environment for this, and this being higher-order thinking, and specifically the practices and processes, and what the Next Generation Science Standards are requiring of educators and districts?

Scott Morrison: Again, I think if we think about all the things that we've talked about, I think a big part of our focus needs to be on making sure that we provide the high quality professional development to our teachers that they deserve. We can't expect them to do these things without the support from an administrative team and without the tools and the resources that they need in order to do this.

I just love this picture, and it's a picture that I found on Google. I really think we're in a very unique time in our field right now. If you think about it, you have 20- year olds working with 30 year olds, working with 40 year olds, working with 50 year olds, working with 60 year olds, and there's power in that. That's that personal point. The strength of our profession right now is really the intergenerational dynamic of our teaching force.

To me, the knowledge piece is the 20 year olds coming out of college. They come into our classrooms. They come into our schools, and they have a ton of knowledge. They have collected a lot of dots, right? Our veteran staff — the folks who have been at it a while — they've connected those dots. They've taken all of that knowledge that they've had and they've connected it all. To me, there's such power in grasping that. You talk about the practices of education and engaging our teachers in the practices of education. That's what we should be harnessing, right?

That's the work that we should be doing now is really trying to do the best job we can of matching up the newbies fresh out of college with the experienced folks who have been there a while, and start to have those conversations and create a forum for that to happen. We do that often here. We'll get a handful of subs for the day, and we'll free people up, and we'll have a day where we connect the veteran folks with the newer folks in there to get them to pass on some of that wisdom while the younger folks are passing on some of that new knowledge that they've learned. Some of these new techniques and things that they've learned in their classes.

If we do that — if we really provide that training — then our teachers are modeling these best practices, and then they have a better idea and understanding of how they can run and operate in their classroom. I think that's another great way to do this.

There's another quote. This one isn't mine, but I love it. It's just so poignant, I think: "We need to prepare students for their future, not our past." I think oftentimes, when we think about education, everybody's been through it. Parents, everybody who in the world has been through some form of education, whether it's public or private, and someone has an opinion on it obviously, because they had been through it and they say "But what I had worked."

That's great, but we're not preparing kids for that. We need to prepare them for their future and I think we have an idea of that future's going to look like. Now, it's up to us to figure out: How do we figure out how to get there?

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm (affirmative). It's interesting. A quote that comes to mind, that idea of, we don't want to teach to the past because as an innovation economy — as an economy that relies on solving problems is really I guess what innovation is, right?

Scott Morrison: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Francis Vigeant: Some of those problems are social. Some of those problems are technical. Some of them are physical. Some of them are not. Whether it's software, whether it's a machine, whether it is a communication mechanism and all these sort of things, that's where things are going. It is very much a different world than even 20 or 30 years ago.

I see exactly what you're saying that people... As a teacher myself, I have a very similar story. Started in an urban district, spent time there as a high school math teacher. Then went on to be an elementary- and middle-school STEM specialist and taught there for a number of years, also as part of my role here at KnowAtom early on. You see folks get stuck in the past. Almost a prisoner of the past.

The quote that comes to mind — and I believe that it was JFK, he had this quote that, "Your rights end where somebody else’s nose begins." I hope it was JFK. If it wasn't JFK, I stand corrected. I think about that, and I think about how as an educator it's easy to see what has worked and get set up with your curriculum and materials and everything soup to nuts. You've done it a number of times, and you know how it works and to stick with that and almost feel like it's your right to stick with it because it worked in the past and so on.

I see that like, "Where does that end?" I would change his quote to say not, "Where someone's else's nose begins," but, "Where somebody else's opportunity begins." I see that as the student. Their nose is their opportunity, and to be a prisoner of the past is really to extend into potentially somebody else's opportunity. I think that's what strikes me so much about that.

Scott Morrison: Yeah, and you talk about innovation. I think — again I'm not going to recall who says this one, but it's one of my all-time favorites, and I think again it's very visual: "Innovation lies at the nexus of different knowledge domains."

I love that quote, and if you think about it, you think of the different knowledge domains that are out there, that's where innovation lies. How do we travel and bring those together? How do we bring those knowledge domains together and figure out what those innovations are? How can we innovate education and figure out better techniques of how we're delivering instruction?

I think it transitions nicely to this slide. You actually introduced me to this TED talk, and it's absolutely one of my all-time favorites. I've used this in a number of trainings since you first had sent that along to me. Shared the information with me.

Francis Vigeant: I was just going to say, Simon Sinek, right?

Scott Morrison: Yeah. It's Simon Sinek, and after this webinar, if you Google “Simon Sinek TED talk,” I highly recommend you watch this. It's a business practice, but the implications for education I think are profound. Basically the business practice that we talked about is what's called the golden circle theory. You can see the theory there, the circles on that little white chalk paper that he has there.

He basically says, in the business world, businesses that are a commercial failure spend a lot of time talking about the what and a lot of time talking about the how, and they never get to the why. He gives a great example of I think Tivo. He said, "Tivo, that's a product that allows you to pause live TV," and he said, "They weren't as successful as they could have been because they basically came out and said what their product did and how it worked," but when you talk about the why, you connect to a limbic system of a person, which is their emotional center.

That's when you really grab their attention. He then gives a conversely different experience where he talks about Apple. Apple — all they talk about is the why. They say, "You want to integrate every aspect of your life? Do you want to integrate text, and phone, and video, and chat, instant messaging?" and you're like, "Yeah, of course I want to do that." "Then you should buy our product." "Okay, I'll go buy your product."

As I watched this video, I thought about school, and I thought about the work that we do in our classrooms, and I visit classrooms, and sit in classrooms, and talk to teachers. I use this video and we talk about this video all the time. We talk about all the principals and the teachers. Let's just take a history class for example. We might talk about what the American Revolution was. We might talk about how it happened, and then, right near the end of the unit, we might finally have time for the why.

The real learning happens at the why. I think we need to start with the why. If we can start with the why when we're training our teachers, that goes back to the idea of making sure that our teachers have the skills and knowledge necessary. We need to start with the why: "Here's why this is important. Here's why I pulled you out of the classroom today to have this professional development day.” We should always start with the why.

Too often, we spend so much time on the what and the how. I feel bad now that I know this video, because when vendors come in and they want to sell me a new product, I ask them why — "Why do I want this product?" — and oftentimes, I've got to listen for it in conversation. I listen to most people. Most people talk about what and how. And real true learning, in my opinion, happens how important, but the real learning is up to the why, and I think if we can flip that and think about our instructional lessons in our classroom and focus on the why, again, I think that would be powerful.

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm (affirmative). It's interesting because, in thinking about professional development and when we are talking — we being KnowAtom — we are talking with folks about the kind of questions that we ask of students in class. It's really interesting to see the trend or the default to what, which it almost presents itself as a fill-in-the-blank. You can almost picture somebody saying, "Tell me what I want to hear."

Scott Morrison: Exactly.

Francis Vigeant: Back to that traditional model where, "I've told you something, tell me what I've told you." It's exactly that. The student's being asked to be in that role of handing back what was handed to them, but when you transition to those higher-order questions — the whys, and even the hows, depending on how that's framed — you really start to change the purpose of instruction, I think.

I was going to ask that in terms of your thoughts about the next generations model of instruction, and I wanted to get your thoughts on this. This is a diagram we've used a lot. The idea that students are developing practice skills and that the Next Generation Science Standards are changing the role of the teacher from being the one who tells what and asks what and instead the one who adjusts supports so that students can develop those practice skills and then apply them through the processes to the content so that they're actually developing it, and using it, and engaging in being scientists and engineers.

What's the relationship you see to why and starting with why here?

Scott Morrison: Right. I think there's many connections to the why. I think they did a really nice job in the Next Generation Science Standards of articulating the practices of science and engineering, getting to the disciplinary core ideas, and then getting to the standards connections. The three dimensions. When you think about the three dimensions of the Next Generation Science Standards, when you think about those dimensions, it really builds towards the why that this information is important.

To look at your diagram, which — hold on, there it is. Sorry, just tuned out on me for a second. They why gets to what's no longer people talk about the stage on the stage. It's no longer the teacher saying, "Here's this information that I'm going to pass from my notes to your notes." It is more of an iterative process where, as you can see with the dashed lines there, everybody's going through this together.

The teacher is more of the guide on the side, so to speak, and it's a little messier. There's no question about it. It's the kind of thing where you have to be willing to give up a little bit of control in your classroom. I think we often confuse classroom management with just order and quiet, and I don't really view classroom management that way. I view classroom management as, "Have you built an infrastructure in your classroom where kids are able to engage in learning experiences with each other, with the teacher, with the materials?"

It's not going to be rows and kids sitting quietly. It's going to be kids manipulating ideas, and thoughts, and materials, and your standing and your information is to deliver why this is important to them. I think that the buy-in there will be in much greater demand.

Francis Vigeant: I wanted to take this even more concrete in the second and ask in terms of Simon Sinek and that golden model here of the why.

Scott Morrison: Yup.

Francis Vigeant: The golden circle. The why, the how, and the what, but I guess because so many folks don't have a sense probably of Manchester-Essex regional, and how your students have done, and how your teachers have done actually moving into this next-generation model. I know there's a lot of different tools with multiple hats and multiple intelligence, a lot of other training that has been a part of your district's culture and developing that.

I want to think a little bit more about that, but I want to point out to everybody — I'm going to bring it up here so that folks can see. Your district, as a regional district, is double... Let's see here... Essentially double the Massachusetts state average on standardized testing for advanced and proficient students, and that says a lot.

The State of Massachusetts basically averaged 50% advanced and proficient. In your community, you have folks who are performing at, what is it? Eighty percent almost here between different towns and whatnot. You can actually see the point of change as well. I think with 2010, that was the last test year without KnowAtom, and I think we came in as a lot of these shifts were taking place. Then how your community has taken so much on, and not only been able to improve their performance, but actually sustain it as well.

When you're trying to get these types of gains, how does that connect to why, what, how? At a district level, where does that innovation come from, and how do we accomplish it if as a district leader? I'm looking at the Next Generation Science Standards and saying, "Okay, I've got a bunch of teachers who do define effectiveness through students in seats and order over chaos and so on and so forth." A lot the challenges that you've brought up, what do you say to them?

Scott Morrison: I would say to them that there's this notion of when you think of just an organization, whether it be a business, or whether it be a school, or a private practice, or whatever the case may be. I think schools need to envision themselves as continuously adaptive organizations. I don't know if we've been a hundred percent successful at that over the course of time that public education has been existence. I think when you think about a continuously adaptive organization in viewing your school district in that way, you're a school district, but you also are a continuously adaptive organization.

You're adapting. You're changing to the needs of the students that are in front of you, based on the world that we live in today. I think if we look through that lens, that's step one. It's that mindset shift in terms of looking at it as a continuously adaptive organization. There are reasons why some of these old, traditional department stores that for hundreds and hundreds of years or at least a hundred years, rather had existed and are finding themselves maybe closing: It's because maybe they haven't been continuously adaptive. I think we need to think about education that way.

I think that Step One is really having that conversation. If you want to be a world-class school district, what does that mean? I think it's thinking of yourself as a continuously adaptive organization. Everything flows from that because if you make that decision, you're saying to yourself, "Okay, we want to be on the cutting edge of what we know needs to happen," and you have to build culture for that. That's not going to happen overnight, but it's like that old saying, "How do you eat an elephant?" and it's, "One, bite at a time." I think it's very true in this as well.

Concretely, if we use KnowAtom as an example, I had a couple of go-getter science teachers at the elementary level that, I knew if I put a product in their hand, they would become the AmWay or Tupperware representatives, so to speak, and they would do much more convincing than I would ever have to do in terms of getting other people onboard. We brought those two folks in, we gave them the professional development that they needed so they had the support and the tools. Again, another key feature of making yourself a continuously adaptive organization is making sure you're giving people the tools and the support that they need.

Sometimes, I think probably one of the questions is going to be, "Well how do you afford all that?" We have to really think about what's important, and are you doing things in your district that is preparing your students for your past as opposed to kids' future? Then you need to maybe make some of those hard decisions.

We got the program. Again, we'll use KnowAtom as an example and the hands of those couple of teachers. They tried it; they worked it out. We had other teachers rotate in to see what was happening.

The teachers who were teaching it understood the why of why we were teaching in this way. Why we were thinking about it's not just science on Friday from 2:00 to 2:30, where there's a very step-by-step experiment, and, "If you get to the end and it works great, and if it doesn't, sorry to hear that." It's more of, "If you fail and it didn't work that's great. That's actually a good thing. Let's go back and see why it didn't work. Where along these practices did it not happen as it should have?" That becomes that reflective part of it.

Then from there, the program — again if we use KnowAtom as an example — we have advanced it to an entire grade level. We said okay, and then we advanced it to another grade level, and over time this has taken, if you go back to that chart there, Francis, if you don't mind. The Essex one. I think Essex is a good example of this.

Yeah, so you can see there that the trend overall is up. It took some time, over four or five years or so, and going from less than 60% advanced to proficient over to almost 80% advanced-proficients. You can see that a little bit along the way with that sort of peaks and valleys and any sort of implementation. If you look at the whole, we've had real positive growth, and the needs improvement and the wanting have gone down. I think, to me, it's just if we can explain to the teachers the why, I think too often as administrators, we just say, "Here, do this." "Why?" The why we say is because of the federal mandate, and it's like, "Well, that's really not the best why in the world."

I think we can meet the federal mandates, and we can do it in a way that we are preparing our students for this unknown future that they're heading into, because we're building this infrastructure set of schools, and this is a great slide that you just put up because, articulating the values of your school district, sitting down as an administrative team, and with teachers onboard, and really having those bigger conversations of, "What do we value? What do we hold near and dear to our heart?" so to speak, in terms of what we know to be right about education and the way that we want to move forward.

Then you begin to design, and you can even take that to the way a unit of study is designed in your classroom. It's the same thing. "Here are the standards. What's the mode of instruction we're going to use? Here's the details of execution." That's when a model fits, I think — with district innovation and also classroom innovation.

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm (affirmative). It's interesting; I wanted to ask you about this diagram and I'm not sure... The next one here, I'm going to ask you about this.

I think about it, and I think about when we sit down with administrators and teachers. Earlier, I think you mentioned learning blocks or at least classroom visits and I think, "My goodness, superintendents are vital to a district; they build budgets and school committees, school boards and all of this." Principals — and they are managing principals — principals are in that role for their building, and people may say, "Well, I don't have budget authority," or something like this, and okay, there's going to be some differences here and there, but I think about it and I have to say that, in our experience, very few principals realize the role that they have in establishing the values and culture of their building.

I have to say — and I think this is the hardest thing for folks outside of education to understand — that you can have a school district, especially the larger a district becomes. If you have a one-building district, that's one thing. Everything is pretty direct. You have one principal, one superintendent, and so on. You go to a 10-building, or 20-building, or a 100-building, or even a thousand-building district, and what happens is that each of those buildings are with its own unique principal, has its own… oftentimes own unique set of values, and everything forms from that.

I think it's almost a passive process, unfortunately, so many times. I wanted to ask you, in terms of that idea of values, I think folks might think of this as like a positive psychology, fluffy thing: "Oh yeah, we have a mission statement; it's on the wall. We did that because that was a mandate. That was something we did back when whenever.”

What I guess I want to point out about this is that if your values don't align, what does that mean for your mode of instruction? The details of how you execute. Again, I don't mean to be talking in circles, but I've had the opportunity to meet your team. If somebody joins your team and their idea of instruction is worksheets and students quiet in their seats in rows, I think that would bother people. Am I wrong about that?

Scott Morrison: Yeah. I mean, again, we wouldn't hire that would have to have the hiring table. I don't think that person would make it into it, but let’s just say that did happen, yeah that would be...

Francis Vigeant: Say they did it.

Scott Morrison: Yeah, that would be certainly problematic. In terms of convincing, that doesn't match what we have envisioned. I have something — I'm sitting here at my desk right now, and the field that the kids walk off for graduation is right outside my window, so to me it serves as this great visual reminder every day when I walk into my office. I say to myself, "The world that we're preparing these kids for when they walk off the field, what is it they need to know and be able to do?” If it's something that they can maybe quickly look up, we might not have to spend too much time on that in the classroom.

Again, some rote-memorization kind of a thing. Again, if we can focus more on this idea of engaging kids in higher-order thinking and engaging kids in the practices of their educational journey, I think we have a much better chance of having them succeed later on in life. I think that's when you talk about the values, and you talk about the mode of instruction, you talk about the details of execution, again you have to have a little bit of a long view on this, and then there's going to be a slide coming up here that I think that really speaks to this.

Give me that quote slide, because that's actually pretty fitting with your Arthur Ashe quote. This one here. To me, we could have started with this quote, we could have ended with this quote, we could have put this quote in the middle, and I think this has to be a huge takeaway for today: "Start where you are, use what you have, do what you can." I think that's just so crucial, because everybody is at a different point.

It can sometimes seem extraordinarily overwhelming to think about — "Oh my goodness. Wait a minute. I have to change the entire culture. I have to do this. I have to change my instructional practices," or whatever the case may be. Anything worth doing is going to be worth the time it takes to it. If you just make one change. You make one or two changes this month and you make one or two changes a couple months from now. Then, at the start of next year, you make another couple of changes. Then, over time — again, it's not all going to happen by March 1st — all the things that we talked about today.

You'd have to go out to the principals and having all the principals that have different values. That could be another whole webinar. We had talked about just building those relationships and having those relationships with people. All of that takes time.

I know we always feel a little bit under the gun, so to speak, in terms of, “We need results now,” and it's enough to keep school boards at bay and try to convince people that, "Look, we're on the road, and we're doing what we can, and I understand those challenges." I do, and I think you just have to keep chipping away at it bit by bit, and I think this quote is really a guiding light to us as we think about the work that we do here.

Francis Vigeant: I think you bring up a great point, and then I think that there are a few books that I would recommend to people along the lines of a lot of what we've talked about today. One being Tribal Leadership, which I did with Logan.

The idea of how — because each building in a school district, it's its own tribe with its own culture and has its own method and way of communicating. You really need to understand that I think from an administrative perspective. It would be one thing that I would recommend, and I know you mentioned Simon Sinek; he has a few books as well.

Scott Morrison: He does.

Francis Vigeant: That I don't know if you would recommend, but I think are key to some of these ideas.

Scott Morrison: I think I know… Maybe we want to do some questions. Maybe I'll end with this and I'll deal with that. This sort of visual, it's the farmer who says, "I don't have time to build a fence; I'm too busy chasing all the cows." It's like, "If you built the fence, you wouldn't have to chase the cows." I think, when we think about the work that we do in public education, are we running around chasing metaphorical cows when maybe we need to build that fence, so to speak, and more define what it is and who we are and what we want to be and where we want to go?

Francis Vigeant: I think that's a fantastic point. For folks — I know we have folks out there still with us, and we'd like to take some questions if you're on the live session. We have probably five or 10 minutes for questions here, so if you have some questions and would like to send those over, you can type them in. I know folks may even be listening in groups. They may have to gather a few questions from the folks at your table.

While we're waiting for a few questions to come in, one of the other things I guess too as we think of that you mentioned several times is thinking of Next Generation Science Standards as a combination of short and long play. Taking the long-term view of things and a lot of what we've talked about. When you think about things like organizational change, I think about a book that's actually a business book that was written by Tony Shea of Zappos shoes who has become very famous for culture.

Scott Morrison: Flat organizational structure, I think.

Francis Vigeant: Flat organizational structure, and the name of the book that I'm thinking of is Delivering Happiness. It's a business-oriented book, but a lot of times, he's talking about hiring for culture, and I think maybe one of the reflections here is that in education, we can hire new people for culture, but we have to start with where we are and we have the cultures that we have, and so some of the challenge here is really… and I think you gave some interesting strategies about finding your champions and feeding your champions and helping them to become agents of change. I think the theme there is really about empowerment. Is that the case?

Scott Morrison: That's totally the case. That's a successful model I've seen applicated in many districts, where it's that grassroots efforts of finding some people who have that interest, and then I always think of it as chatter. The chatter in the hallways and the chatter in the teacher's room. And when that positive chatter builds, people tend to be a little bit more interested in maybe what is happening. Conversely, when the negative chatter builds, if people are often hearing that, "Oh, that copy machine always breaks," or this, or that, or whatever, then people think, "Okay, never going to use our copy machine again," or whatever the case may be.

I think, yes, when you can plant those seeds and tend to them and let them grow, all of a sudden, by shining a little bit of light on them, they really began to flourish. Other people begin to see them, and they're interested in being a part of it, so I'm sure many people have used that kind of strategy before, but we have certainly found that to be very successful.

Francis Vigeant: Great. Once of the questions we have here is — it sounds like a stakeholder groups, so: "Outside of teachers, who else is key to this equation transitioning to Next Generation Science Standards?"

Scott Morrison: Building leaders. That's huge. Having principals onboard. I think that's a key piece, because everyone is very busy. Everyone has a job for whatever function they're in. Whether they're teaching or whether they're a principal, or my role, or a superintendent. Whatever the role that you're in, we all have a million competing demands every single day and are pulled in a million different directions. It's easy, I think maybe, for a school principal to just be like, "Oh, great! Next Generation Science Standards. Sounds good. Let me know if I can help."

I remember being a principal and saying something to that effect to my assistant superintendent at that time. Just, "Great, you're on it. That's super, because I got a lot going on." I think it's key that, again, it's going to have to be its time. It's going to be taking the time, and it's going to be based upon making sure that you can find the time to do this, but making sure that the principals and the school leaders in the building have a solid understanding of — they don't need to know maybe that this piece of content is taught in third grade — but having an understanding of how the science standards are put together, the disciplinary core ideas, the practices, and really getting into that part of it.

I think the more they understand that, then when they go into classrooms and they see an action, that will just further reinforce the training that you give someone. I think that's a key group.

Francis Vigeant: Along those lines, there's another question that essentially is asking, "Is the Next Generation Science Standards basically sacrificing content for inquiry?" What are your thoughts on that? Maybe the relationship?

Scott Morrison: Yeah, that's a great question. To me, the content becomes the place to practice the inquiry. I don't think that's one or the other. I think the content — whatever the content is — the content is just a place to continuously practice the skills that you're trying to, again, if you think about that infrastructure skills that you're trying to pull back from Grades 12 all the way down to pre-K.

Whatever that is in your district or your town, or your state, or whatever, whatever you decide it's what you think kids need to know to be able to do and they get into the world. The college, and career, and military, or wherever they may be heading. I think you're not sacrificing content for inquiry; you're actually using content to practice the inquiry.

Francis Vigeant: Yeah, so they're not mutually exclusive?

Scott Morrison: No, there's not at all.

Francis Vigeant: This one here, let's see… This may be a little different flavor of something similar, but it seems different. "Where do you recommend starting, and what has surprised you most as you've gone through this process?"

Scott Morrison: Do you know if that’s a teacher asking or a principal or a superintendent?

Francis Vigeant: I don't know. I would assume it could be any of the above. Maybe extend it out to all three.

Scott Morrison: I would say then, if you are a district administrator or a school administrator, I think a great place to start — and this is not a punishment kind of thing; I think again this goes back to the culture of your building and explaining the why to people at a faculty meeting. I think taking that audit of, “Where are we spending our time? Let's take a look at how much time are we devoting currently to science instruction.”

Oftentimes, science or social studies get the short end of the stick, I think, because of a lot of the state and federal mandates that we have out there. I think that's a fair thing to do. I think if you explain to people with these Next Generation Science Standards, we really have an opportunity here to develop the critical-thinking skills of our kids and really, if you think about innovation lying at the nexus of different knowledge domains, and figuring out how we can do this and really explain the why to people, then I think taking that time audit and figuring out where you're spending your time, so I think if you're a district leader, you start there.

If you're a classroom teacher, think about the current unit of study that you're on. Think about one way that you could tweak it that you could maybe incorporate with a bit more of this idea of higher-order thinking and having kids engage in the practices. The beauty of it is, no one's going to know. The kids aren't going to know if you did it wrong. If you mess up the first time or you make a mistake, the kids aren't going to say, "Well, wait a minute, that's not the right order of the practices." Right? It's okay to take that chance, and you're not going to damage the kids if you maybe went out of order or you tried the engineering practices in some way and it didn't work.

Clearly, if you're using chemicals and electricity and things like that, you've got to be careful, but just in terms of engaging kids in the practices, I think certainly just do one thing different. Really use that Arthur Ashe quote as a guide and just, “Start where you are, use what you have, and do what you can." If you don't have a budget — Francis, I remember at STEM Squared, I don't know if you can quickly remember this, to out you right on the spot here, but you gave a good example of you can do an experiment with a trash barrel, a candle or something. What was that one?

Francis Vigeant: Yeah, I don't totally remember, but the bottom line is that I guess I think of it as somebody once said to me that if you have your mind, you have everything. Nobody can take that from you, essentially. You know the thinking is free, and it's extremely valuable.

Scott Morrison: Right.

Francis Vigeant: So to use what's in your recycling bin. To use what's in your desk; there's so much there. If that's all you have, you've got a lot, because you can think about it, and it connects, just like everything in science. States of matter, Earth science, life science — all these things are interconnected, and you can find rocks and dirt outside your window, and you can find matter in the trash can. All these sort of things. I guess maybe that's where I was going with it, but I think you bring up a really great point. You have to start somewhere.

Scott Morrison: Right. One small change. Just say to yourself, “By February 18th,” whatever — pick a date and then hold yourself to it — "I am going to try this.” Then you try something else, then you try something else, then you're in the teacher's room. You talk with the teacher about how you did this today, and it was a little bit different, and boy, the kids really seemed engaged." That's how it builds.

Francis Vigeant: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think that's the key piece of it, if anything; I think Next Generation Science Standards and the practices and even what you've described in the recommendations you've made, it's incredibly engaging and has the potential to be incredibly empowering, but it's only if you take it.

Scott Morrison: Correct.

Francis Vigeant: I think about that idea of starting with the why that you brought up from Simon Sinek. If we don't start at the why and instead we start at the what, what's the purpose? What are we here? How are we engaged? How are we empowered? I think you brought up...

Scott Morrison: Brought up some really good ideas, yeah.

Francis Vigeant: It is. Well, Scott, I really appreciate your time. I know we've gone a little over.

Scott Morrison: Thank you, Francis.

Francis Vigeant: Oh, you're welcome. Thank you. The honor is ours.

I wanted to point out to folks a few things before we sign off. One being, if you'd like to take a look at some of the resources Scott's district's been using and others, there are some samples on our website of our materials, but again, it's only a small piece of the puzzle. There's much greater and I think that's the thing.

There are standards, then there's curriculum, and then there's instruction. Each of these pieces — and there's differentiation of instruction. Each of these pieces plays a such a vital role. This is not a pitch by any means. There are pieces that I hope stay connected. Even through our blog, blog.KnowAtom.com, or on Facebook — Facebook.com/KnowAtom — or even on Twitter.

We did do a webinar recently on designing effective Next Generation Science curriculum where we really unpacked not only what's in the Next Generation Science Standards, but also a lot of the considerations that I think take into account a lot of what you've recommended, Scott, in that, and folks can access that by going to info.KnowAtom.com/upcoming-events.

I would recommend too, if you're on LinkedIn, reach out to Scott and connect with Scott, because I have to say, Scott, I really appreciate your view and your district's work, like all our clients, but I have to say, the wonders of technology and Internet is that we have folks from all over the United States and even the world who are able to benefit from your experience, and I appreciate your taking the time to share it with us.

Scott Morrison: Sure. Happy to do it.